I am interested in the relationship between

justice as a means and as an end because those aspects separately and their

standing with respect to one another are integrally—that is to say

inseparably—involved in how we think about ethics generally and in specific

cases.

For instance, recent, disturbing race-related violence by police officers toward certain citizens in the United States and then the assassination of 5 Dallas officers and the wounding of many other police and civilians raised complicated questions about what is right, fair, and valuable in itself, about the nature and extent of contemporary prejudices, and about the use of violence in service of conceptions of justice. Similarly, the recent decision by the U.S. Justice Department and its Federal Bureau of Investigation not to indict Hillary Clinton despite the overwhelming evidence of her violations of standard federal security procedure strikes many observers as unjust. This is so not only because the decision seems to contravene obvious desert (the FBI does not doubt what she did), but also because, notwithstanding Director Comey’s (knowingly erroneous) denial that positive intention is required for a violation of the law, it raises questions about whether some supposedly greater purpose like social and political harmony in an election year outweighs the upholding of the law for its own sake or even as a deterrent to future security mismanagement. Is justice, we might wonder, something good in itself and to be pursued for that reason, or because of the ranked purposes that it may serve?

United States citizens in 2016 are not the

first persons or society to entertain these questions. The ancient Greeks anticipated contemporary

Anglophones in this as in many areas, particularly Plato. It may be timely and to our profit then to

ask this: Is justice in his Republic an intrinsic and an instrumental

good, as Socrates promises to prove to his interlocutors? Or does

he only show that it is an instrumental good, in which case Glaucon's

ventrilloquism for Thrasymachus (i.e., voicing the latter’s position for the

sake of argument) is more on the mark?

In what follows I wish to explore this important

question about justice as an instrumental and a final good through the lens of Plato’s

Republic. Socrates contends that justice is both

intrinsic and instrumental. How does he

argue for that conclusion? How might this help contemporary societies

understand both justice and the proper relation and pursuit of various ethical,

social, and political goods?

An Overview of the Argument in

the Republic

I have always been drawn to Plato’s dialogues,

perhaps because of the drama of the conversations between Socrates and his interlocutors as

they explore various questions. The central question in the Republic is what is

justice. I want to share my thoughts about two specific aspects of the Republic that I believe will

also simultaneously identify

and distill Socrates’ central claims about justice: that justice is (1)

instrumentally good and also (2) intrinsically good. This

is to say that justice produces good consequences, and justice is good for its

own sake. Chiefly,

according to Socrates, justice in the individual

is that state when all three parts of the person – rational, spirited, and

appetitive – are fulfilling their proper function to create a condition of

harmony, which leads to right actions. From

this it follows that it is never a good idea to be unjust: disharmony

(i.e., injustice) results, and doing justice for its own sake is not even a

consideration.

|

| Title page of the Republic (Codex Parisinus graecus) |

Rather than summarize the

entire dialogue here, I only wish to highlight the most important points as

they relate to justice. In this vein, it may be helpful to rehearse some

background information. A man named Thrasymachus interjects

early on during Socrates’ conversation with another man, Simonides. Thrasymachus is

called a sophist, which at the time referred to someone who was hired to teach

generally wealthy people or their children how to succeed in argument so as to

excel in politics, the ruling/governing of the commonwealth. This feature

of the dialogue is important to note, because Thrasymachus answers

Socrates that justice is the advantage of the stronger.

By this Thrasymachus means that one who acts justly will thereby become weak and that this weakness accrues to the benefit of the one who acts without scruples, the one who acts unjustly because he thereby gains an advantage over the person who acted justly and became weakened. In one sense, justice is what is enacted in policy by those who rule strongly (might makes right). In another sense, justice is that which benefits the unjust, although, when Socrates presses him, Thrasymachus must take a circuitous route to defend that position: justice does not benefit those who act justly; justice benefits those who act unjustly: “Come, then, Thrasymachus … You say that complete injustice is more profitable than complete justice? I certainly do say that” (Republic I, 348b-c). Socrates denies that point. And the rest of the dialogue in the Republic is essentially Socrates’ attempt, through conversation with Glaucon and Adeimantus (Plato’s brothers) who take up Thrasymachus’ position for the sake of argument, to prove that justice is both good in itself and more profitable than injustice: “I myself put [justice] among the finest goods, as something to be valued by anyone who is going to be blessed with happiness, both because of itself and because of what comes from it” (Rep. II, 358a).

The Central Analogies of

Harmony: Justice in City and in

Individuals

Adeimantus appeals

to Socrates to address just these two points: not only the consequences of

goodness/justice, but also its intrinsic goodness (Rep. II,

366b). In response, Socrates suggests that they zoom out their

conversation to look at justice where it exists in large scale, because that

will help them to identify it on a smaller scale in more particular

cases. Therefore, Socrates introduces

the idea of looking at justice within an ideal city first (Rep. II,

368d). Then it will become more apparent what justice is between

individuals who live within the city. Moreover,

individual people are not self-sufficient. They live in community and

need others to complete tasks that they cannot do easily for themselves.

Flourishing as individuals is related to flourishing in society. Socrates sees

the city and the individual as operating similarly as regards justice within

its proper sphere. Justice

in the city and justice in the individual are both

related and analogous. This

is one key feature to note of Plato’s account of justice in the Republic.

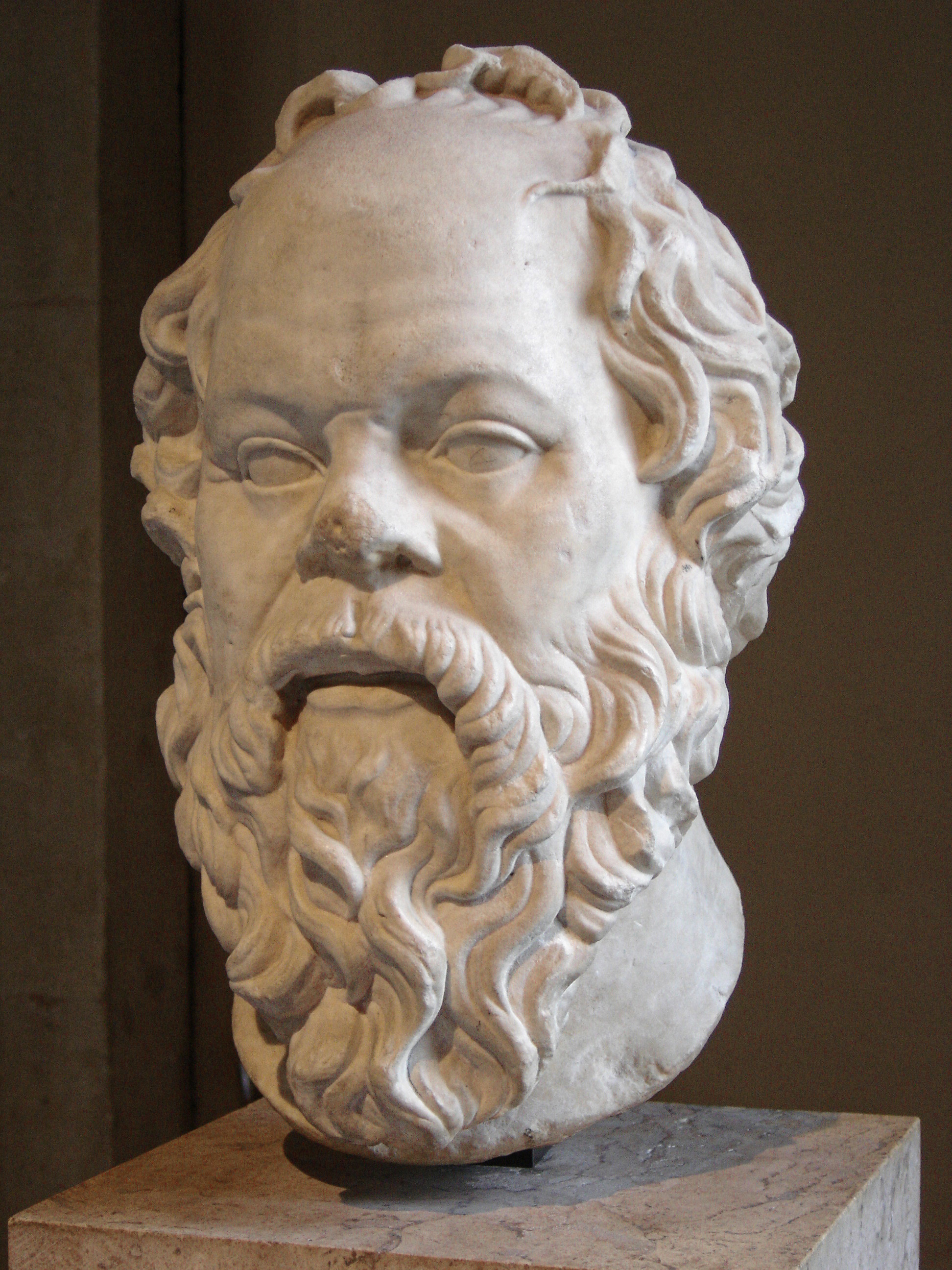

|

| Socrates (d. 399 BCE) |

Socrates outlines the workings

of his ideal city in Books 2-3, and in Book 4 begins to explore more properly

where justice is found within it. Socrates identifies four key virtues

that will thrive in the city: (1) wisdom, (2) courage, (3) moderation,

and (4) justice.

The first three virtues correspond to the three chief

class divisions within the city: (1) wisdom/rulers

who oversee all, (2) courage/guardians who

defend the city from threats, and (3) moderation/the

auxiliaries restrain themselves to devote themselves to their particular craft

or trade. Justice

is integrative or all-encompassing virtue.

As G.M.A. Grube notes,

“Justice means the harmony that results when everyone is actively engaged in

fulfilling this role and does not meddle with that of others. Injustice then is

precisely that kind of meddling” (Plato’s Republic, translated by G.M.A. Grube [Indianapolis:

Hackett, 1974], 85).

Now Socrates moves to the

analogy of justice as it relates to the individual, or the soul. There are

conflicts in a soul’s intentions, and this helps to prove that there is a three-fold

division within the individual, just as the city has three divisions. Justice

in the individual, as in the city, will keep all three parts flourishing in

concert, not competition, with each other. The

three parts of

the individual mirror

those parts and functions within the ideal city: (1)

the reasoning part (corresponding to wisdom/rulers), (2) the spirited part

(corresponding to courage/guardians), and (3) the appetitive part

(corresponding to moderation/auxiliaries). Justice

in the individual is, analogous to the city, when each part of the person is

discharging its proper function or role.

Such harmony among the parts of the individual, as in the city, will produce or

result in just actions:

And in truth justice is, it seems, something of this sort.

However, it isn’t concerned with someone’s doing his own externally, but with

what is inside him, with what is truly himself and his own. One who is just

does not allow any part of himself to do the work of another part or allow the

various classes within him to meddle with each other. He regulates well what is

really his own and rules himself. He puts himself in order, is his own friend,

and harmonizes the three parts of himself like three limiting notes in a

musical scale—high, low, and middle. He binds together those parts and any

others there may be in between, and from having been many things he becomes

entirely one, moderate and harmonious. Only then does he act. And when he does

anything, whether acquiring wealth, taking care of his body, engaging in

politics, or in private contracts—in all of these, he believes that the action

is just and fine that preserves this inner harmony and helps achieve it, and

calls it so, and regards as wisdom the knowledge that oversees such actions.

And he believes that the action that destroys this harmony is unjust, and calls

it so, and regards the belief that oversees it as ignorance. (Rep.

IV, 443c-e)

There seems to be implicit in

the argument the idea that disruption to this harmony (i.e., injustice) results

in less good for the city and for the individual than if harmony (i.e.,

justice) prevails. This is the consequentialist side of the argument for

justice that Adeimantus had

requested. The city ceases to function as well as possible when there is

striving, when cobblers do not make shoes and when guardians do not train for

and exercise military discipline. If rulers seek to make shoes and waste

their wisdom doing what only they as wise rulers can do, then havoc will

result. Similarly, if the appetitive part of an individual seeks

gluttonously to eat as much as one wants, the harmony that is the individual’s

health will suffer. If the striving part of an individual is overly

bellicose, it will lead the individual into conflicts that are unnecessary and

unprofitable. This

is why Socrates believes that it is never a good idea to be unjust: the

lack of harmony, or justice, produces ill effects and violates one’s natural

function.

Justice as an Intrinsic Good in the Republic

So much for the

utilitarian aspect of justice in the city and in the individual. Socrates

has demonstrated that to Glaucon’s and Adeimantus’

satisfaction. But what about the intrinsic aspect of justice, the idea that

it is good for its own sake, or inherently? An inherent good is one

without qualification, that is, without any consequences that result. If

considered in itself, an intrinsic good will be valued for what it is. It

is esteemed above all else, we might say, because of its form, its

nature. Justice is precisely this sort of thing, Socrates contends. Glaucus had introduced

in Book 2 the famous Ring of Gyges example to argue that people act

justly only for fear of consequences, not because they value justice

itself. Socrates uses the city and the resulting discussion to counter

this notion.

Socrates, in this connection,

seems to summarize his view that justice (here called virtue) is intrinsically

good because it affords health to the soul: “Virtue

seems, then, to be a kind of health, fine condition, and well-being of the

soul, while vice is disease, shameful condition, and weakness” (Rep. IV,

444d-e). Justice, or virtue, is what allows the soul to be harmonious, to

be in balance, to flourish and fulfill its nature as soul. This may seem,

on one reading, not to meet the criterial for an intrinsic good, namely, to be

valued for its own sake apart from any effects that it produces. On

another reading, however, Socrates does argue

that justice is valued for its own sake because its expression in the city and

in the individual is valued by the rulers of the city, who educate the

individuals within it, for the mere sake that it reflects the highest Good, the

Form of the Just. The earthly instantiation is a copy of the supreme

good, the Form of the Just. The Form of the Just

(or justice) is valued for its own sake as the pinnacle of goodness, and its

manifestation, or expression, in the city and in individuals is valued precisely because of its perfection.

Socrates points in this direction in Book 6,

when he tells Glaucon that the Form of the

Good gives various virtues their full goodness and makes them beneficial:

…the form of the good is the most important thing to learn about

and that it’s by their relation to it that just things and the others become

useful and beneficial. You know very well now that I am going to say this, and,

besides, that we have no adequate knowledge of it. And you also know that, if

we don’t know it, even the fullest possible knowledge of other things is of no

benefit to us, any more than if we acquire any possession without the good of

it. Or do you think that it is any advantage to have every kind of possession

without the good of it? Or to know everything except the good, thereby knowing

nothing fine or good. (505a-b; see also 508e)

Without the Form of the Good, things which were thought to be known,

meaningful, and beneficial lack just those qualities. Those things are

bankrupt without the Form of the Good.

Various goods such as knowledge or

crafts or skills or personal qualities/actions are proximately virtuous, but

that is only if one exercises them here and now with an eye to the Good -- the ultimate end toward

which the various goods individually and collectively aim, the source of

meaningfulness that makes various pursuits individually meaningful and provides

a context within which their benefit may be evaluated and appreciated.

Some Additional

Thoughts

If my reading of Plato is correct,

then Socrates does fill out his contention that justice is both valuable in itself as the

perfection of the good, and it is beneficial to the individual and to the city. This is an aspect, by the way, that Aristotle will develop in

his own way. Aristotle will also try to sort out

whether the good is such per se or

instrumentally relative to something else.

|

| Aristotle (384-322 BCE) |

His particular articulation of

the good and justice in both the Nicomachean

Ethics and the Politics should,

despite the differences from Plato’s vision, be seen as an attempt to continue,

improve, and complete the basic Platonic project. Their shared project to give an account of

the goods of excellence sees the ethics of the individual as always part of and

necessarily participating in a certain shared social and political context. As Alasdair MacIntyre has noted, for Plato

“justice is the key virtue because both in the psuchē and the polis

only justice can provide the order which enables the other virtues to do their

work” (Whose Justice? Which Rationality?

74). But it remains unclear to me whether Socrates fully or adequately proves

his contention about the dual nature of justice as intrinsically good and

instrumentally good.

It may be that the

unpersuasiveness of the theory of Forms that Socrates supplies indicates that

it is less a proof than a pointer to what is needed to substantiate his

contention. What it points to is that there is needed some standard for

measuring the Good and the just in

order properly to instantiate it in a particular social and political context. Against the sophists, who advocate as justice

what leads to greater advantage, Plato has offered in rebuttal the form of the

argument that at once admits the utility attached to virtues such as justice

but also locates those virtues and their practice in light of some ultimate,

overarching telos that guides the

adjudication of the various embodiments of the pursuit of virtue in human lives

and socio-political situations. For

those of us who are Plato’s justice-pursuing heirs, the form of his argument

may be more important to notice than his theory of Forms (on this point see also MacIntyre, WJWR, 83-84).

Aristotle certainly thought so.

It is what propelled him to work out his own account of what is the

highest good for humans individually and collectively, a supreme good, or end (telos), that it is their natural

disposition and obligation to pursue. This end-goal also serves as a benchmark

for interpreting human flourishing in a way quite different from the flexible

pragmatism of the ancient sophists who, for instance, might advocate a course

of action (perhaps violent, perhaps rule-breaking and otherwise careless) that results

in their advantage over others. Plato

and Aristotle both, in their own ways, invite us to walk down a better path of

justice.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Brief comments to this post are welcome; however, please respect the civil tone of conversation that I wish to cultivate in this forum.