- What was Kant's understanding of the Enlightenment?

- Was Rousseau an Enlightenment figure according to Kant's definition?

|

| Immanuel Kant |

Kant defined the Enlightenment as the philosophical orientation and social movement that promotes rational autonomy. This self-agency is understood as the free human exercise of reason. For Rousseau, the Enlightenment has not promoted but has instead corrupted the free exercise of rational self-agency. Because Rousseau deeply values human freedom, this development troubles him. By diagnosing impediments to the human exercise of autonomy of reason (and arguing for their removal), Rousseau embodies what Kant says is the Enlightenment motto: “‘Have courage to use your own understanding!’” (Kant, "What Is Enlightenment?" in Perpetual Peace and Other Essays, 41) Although Rousseau is not as sanguine as Kant about the Enlightenment that was unfolding in the late 1700s, Rousseau is himself, by his bold exercise of reasoning, an Enlightenment figure according to Kant's view.

1) Kant's View of Enlightenment. The Enlightenment for Kant was human “emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it” (41). Enlightenment reflects maturity, autonomy, and the ability and will to think for oneself. Immaturity has been, if not humans’ natural disposition, second-nature to humans: “He has actually become fond of this state and for the time being is actually incapable of using his own understanding, for no one has ever allowed him to attempt it,” including himself (41; my emphasis). The notion of permission reflects the indispensability of freedom for human rational autonomy to occur: “...if [the public] is only allowed freedom, enlightenment is almost inevitable. ... Nothing is required for this enlightenment, however, except freedom” (41-42).

Freedom is both understood politically (choices others make in the background) and especially individually (choices I make myself). Kant does not believe that in 1784 Europe had been enlightened but that it was in an unfolding age of enlightenment: “As matters now stand, a great deal is still lacking in order for men as a whole to be, or even to put themselves into a position to be able without external guidance to apply understanding confidently to religious [and other] issues. But we do have indications that ... the obstacles to general enlightenment ... are gradually diminishing” (44-45). The destiny of humans is toward progress in knowledge.

Positive progress is underway. It would, therefore, be a “crime against human nature” to erect impediments to future enlightenment (43-44).

2) Rousseau's Response to Enlightenment. That “crime against human nature,” however, is just what Rousseau believes “progress” in the arts and sciences -- and by implication the Enlightenment itself -- has committed. It has not resulted in greater freedom for the human exercise of rational autonomy but in greater slavery. Obstacles are not diminishing because of “Enlightenment,” but increasing.

In the “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts” (DSA; in The Basic Political Writings), Rousseau advances the claim, Michael S. Roth suggests, that modernity was a tremendous mistake because it has deceived humans that they are free when in fact they are now enchained:

While government and laws take care of the security and the well being of men in groups, the sciences, letters, and the arts, less despotic and perhaps more powerful, spread garlands of flowers over the iron chains which weigh men down, snuffing out in them the feeling of that original liberty for which they appear to have been born, and make them love their slavery by turning them into what are called civilized people. (DSA, 3)

In both the “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts” and the “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality” (DOI), it is civilization, modernity—the Enlightenment—that disguises oppression because it creates new needs. No longer concerned merely for self-preservation in the state of nature, humans are lured by and lust after the luxuries that the arts and sciences present. No longer practicing innate sympathy for their fellows, humans are more self-absorbed and less authentic. They have not gained but have lost themselves.

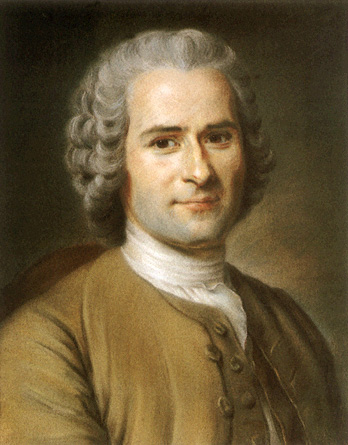

|

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau |

New learning, industry, and property ownership magnify distinctions between natural talents and social status; they highlight and promote inequality. One’s identity is preoccupied now not with who one is but who one wants to become, not autonomous expression but unthinking imitation: “Every one began to look at everyone else and to wish to be looked at himself, and public esteem acquired a value. … The fermentation caused by these new leavens eventually produced compounds fatal to happiness and innocence” (DOI, 64).

It is also fatal to freedom. These are all new forms of dependence. Humans face material and psychological slavery that impedes the free exercise of their rational self-agency: Enlightenment.

What is Rousseau doing by making these critiques? Is he slavishly following Kant’s cheerful appraisal of the virtues of the Enlightenment as it then existed? No. But is it most relevant for assessing whether Rousseau is an Enlightenment figure for him to share Kant’s conclusion about Enlightenment, or for him to follow the path that Kant says is characteristic of it: courageous free-thinking?

Daring to reason, daring to become wise about the world, is precisely what Rousseau has demonstrated himself to be doing. He is independently, without guidance from another, challenging the supposed advances of modernity in order for humans actually to advance in it. Therefore, on Kant’s definition of Enlightenment, Rousseau is decidedly an Enlightenment figure.

3) So what? It may be the case that Rousseau's ultimate position about the Enlightenment differed from Kant's but that his process of seeking understanding was a case study of what Kant says is emblematic of the Enlightenment. The two men had a similar concern for liberty of human reasoning, but they had a different evaluation of what in their day attended it. What does this matter? Let me offer a couple of reasons.

First, it is helpful to map historical persons and their views. Rousseau was initially very much as much an Enlightenment figure in his beliefs as Voltaire and Diderot, friends and mentors of his, before he had a falling out with them and key Enlightenment principles. Asking about Rousseau's more mature thinking relative to the Enlightenment is a worthwhile endeavor. It deepens our understanding and avoids hasty generalizations and anachronisms.

Second, and more basically, exploring the complexities of Rousseau's thinking, and of his position relative to his contemporaries and their philosophical currents, may be instructive for doing the same thing today. We may learn, for instance, how to navigate the positions that one takes in light of the path one takes to arrive at them. This is what I am suggesting about Rousseau and the Enlightenment: he rejected Kant's conclusion that the Enlightenment posed no threat to the political establishment or proper morality, but he agreed with Kant that the courage to reason independently about the world was essential to freedom -- and that is what he exemplified in his two discourses. He did what Kant said was characteristic of a person under Enlightenment, but he did not concur with the gains that Kant said accrued because of Enlightenment.

In the figure of Rousseau, we glimpse the internal and contextual complexities that attend to humans in their times and places: what they think and what they do. This complexity is not the sole province of luminaries whose last names are household terms in educated homes. This complexity is also true of every person whose name we may never know. It is true, as I tend to think about it, of the real people whom we have to labor not to think of as just extras in the movie of our daily lives. These people may be uncredited in our lives, just as are extras in a movie, but they are real people nevertheless.

If we can appreciate the complexity of a writer like Rousseau's position and the path that he took to get there, then we might be able also -- although with difficulty -- to consider patiently ideas and reasoning that seem immediately foreign to us or even seem contradictory. Not all of these ideas and reasons will we conclude are legitimate, but we who like to spend time on complex ideas and arguments in books ought to pay the same courtesy to real people in our lives. What we learn about humanity in historical books should translate into prudent behavior in our daily lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Brief comments to this post are welcome; however, please respect the civil tone of conversation that I wish to cultivate in this forum.